|

Home |

|

Classes |

|

Syllabus / Styles |

|

Biography |

|

Poetry |

|

Photos |

|

Articles |

|

Labyrinths |

|

Storytelling |

|

Artwork |

|

Respects Due |

|

Contact |

|

Links |

|

...with a spirit of self-exploration |

|

Pennine Tai Chi |

|

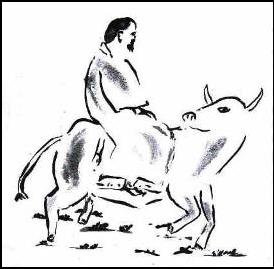

Lao Tzu and the Art of Ox Herding |

|

Of all the great world teachers and philosophers throughout the centuries, Lao Tzu is perhaps the most mysterious and elusive. Much has been written on the lives of the Buddha, Jesus, Mohammed and many others, but of Lao Tzu, we know very little. Some scholars consider that there may not even have been such a person and that the Tao Te Ching is a collected work from the pens of many authors. Others suggest that it is predominantly the work of one person – maybe called Lao Tzu, which has been augmented with folk sayings and wisdom.

History - His StoryCertainly the small amount that we are told about the life of Lao Tzu, makes him sound more myth than man. The traditional stories say that he lived around the 6th Century B.C. After being in his mother’s womb for many years, he was finally born with a beard and looking like an old man. In fact the name Lao Tzu is a nickname meaning ‘Old Master’. Some stories claim that he was born laughing. During his lifetime, he worked at the Imperial Palace as a Custodian of the Imperial Archives and observed the ways of men, the way of nature and the way of the stars. Upon retiring, he decided to leave the Middle Kingdom and headed to the mountains riding an ox. As he reached the Han-Ku pass, the gatekeeper or border-guard, Yin-Hsi urged him, (some say refused to let him pass), until he left some evidence of his teachings, so that those remaining and future generations could benefit from it. Lao Tzu consented and wrote the 81 short chapters of his ‘Simple Way’, which we know as the Tao Te Ching. He then left to head West, never to be seen again.

Mystery - My StoryThe symbolic elements in the tale have many things to tell us. Firstly, to say that he was born as an old man with a beard is most likely a way of saying that he was born with great wisdom. The years in the womb could represent his affinity to nature and being nourished by the Earth Mother. During his life in society, he is not known to have written anything, yet when he arrives at the mountain pass, the gatekeeper obviously knows of his wisdom. It has been suggested that any teachings that he did during his lifetime were oral, or perhaps more likely, that he did not teach in the conventional sense but that by simply being himself, people around him were able to observe his Way. The meeting at the pass also has multi-layered meaning. To head to the west is a universal symbol of going to where the sun sets or to death. (Chinese Mythology calls this the Western Paradise – The Isles of the Blessed. In European Mythology King Arthur was carried westwards to the Isle of Avalon). This image is further emphasised by the customs officer or gatekeeper who takes the role of the Ferryman transporting souls to the other side or alternatively the Gatekeeper to the afterlife of the otherworld. One further aspect of the story, which begs further exploration, is the ox or water buffalo on which Lao Tzu rides.

Ox HerdingThe ox is a universal symbol of strength, benevolence, patience, submissiveness and steady toil. As the power that drove the ancient plough, it was sometimes used as a costly sacrifice in rituals connected with agricultural fertility. In Chinese legend the ox was the second animal to arrive when the Buddha invited all the animals of creation to come to him and in recognition of this, a year was dedicated to it in the Chinese zodiac. In China, the four cardinal points of the compass each have a ‘Celestial Animal’ and an element related to them. The centre is held by the fifth element of Earth, which often has the ‘Terrestrial Animal’ of the Ox associated with it. Oxen are respected and venerated throughout Asia. Their untamed animal nature means that they are considered dangerous when undisciplined but powerfully useful when tamed. Consequently they have come to represent the attributes of the sage and contemplative learning. The Taoist and Ch’an / Zen Buddhist series of ‘10 Ox Herding Pictures’ exemplify this analogy of training the mind and the pictures trace the stages within the awakening of awareness. In some versions the ox / bull starts off wholly black and as the pictures progress it gradually transforms to white before disappearing completely. In essence the pictures represent the sequential steps in the realisation of one’s true nature and the journey to enlightenment. Similarly, the image of Lao Tzu riding an ox is a symbol of his being at one with his own true nature (and it suggests his transcendence and return to the source). |

|

Bull FightingThe bull or ox untamed is seen as embodying the unpredictable and instinctive power of nature and the killing of bulls in the bullring most likely has its roots in ancient sacrifices to a pagan god. Gwynne Edwards describes this as “a confrontation between man and beast, between the rational and the irrational --- played out as a drama in the public domain”. He sees the dark elemental force of the bull as symbolic of the adversary that we must all face at some time in our lives. This encounter with death and danger, in the form of a creature part man part bull, is echoed in the Greek legend of Theseus and the Minotaur. In Indian mythology, it is believed that we must all ultimately face Yama, ‘Lord of the Dead’ who administers justice after death and is often depicted riding a buffalo or as having a buffalo head.

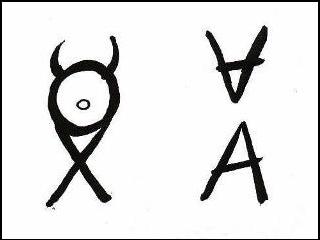

Ox Heads and AlphabetsThe importance of the ox in ancient times is emphasised in the fact that the Phoenicians chose it to represent the first letter of the alphabet and our letter ‘A’ is evolved from this. The original glyph was the other way up like a ‘V’ with a crossbar to give a pictogram of an ox head with horns. Their name for the ox was ‘alef’, but as writing spread to Greece, the symbol was inverted and the name became ‘alpha’. |

Further Adventures of Lao TzuInevitably other stories have built up around Lao Tzu. The earliest writings to mention him were by the 1st Century B.C. historian Ssu-ma Ch’ien. He recounts a tale of a meeting between Confucius (K’ung Fu-tzu) and Lao Tzu, which left Confucius in awe and likening Lao Tzu to a dragon. Since then, tales of further encounters between the two have appeared and these stories usually claim the superiority of the Taoist way over the norms and worldly philosophy of Confucian thought. Some suggest that his journey westwards was really to India where he taught another of his contemporaries, the Buddha, all that he knew. The Taoists say that sadly the Buddha never could get it quite right! Of course, these stories have an element of one-upmanship to them and can probably be taken with a pinch of salt as Taoism invariably has an element of the rascal within it. One amusing story recounted by Osho tells of how each day Lao Tzu went for a morning walk. Often a friendly neighbour would follow him, but knowing that Lao Tzu did not like idle chitchat, the neighbour would keep silent. One day the neighbour had a visitor who also wanted to come; they took a long walk of several hours but the visitor was not comfortable in the silence and felt suffocated by it, so much so that when the sun was rising he said: “What a beautiful sun … look!” Later Lao Tzu said to the neighbour: “Please don’t bring this chatterbox with you again, he talks too much”.

Tao Te ChingLao Tzu’s canon says so much in so few words. Possibly the work was originally shorter and verses have been added, but somehow it arrived at 81 mini chapters. This number has powerful connotations in Chinese numerology (9 being the triple triad – the highest single digit yang number – and 81 being the amplification of 9 times 9). The work became known as the Tao Te Ching, - Tao meaning Way or Path, Te meaning Power or Virtue, Ching meaning Book or Classic. Hence this can be translated as The Classic of the Virtuous Path or The Book of the Way and its Power. It seems that Lao Tzu only wrote this because he was compelled to do so and he began it with the words:

‘The Tao that can be talked about is not the true Tao’.

A warning that words are to follow and although they may point the way, they are not the way, a reminder not to get tied up in the words but to remember the wordless, that which cannot be communicated through language. Berthold Brecht’s Poem on Lao Tzu’s Road into Exile (Final Verse)

But the honour should not be restricted To the sage whose name is clearly writ. For the wise man’s wisdom needs to be extracted. So the customs man deserves his bit. It was he who called for it.

Bibliography The History and Philosophy of Kung Fu by E. C. Medeiros Symbols and their Meanings by Jack Tresidder Looking for the Golden Needle by Gerda Geddes Tao – The Three Treasures by Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh Tao Te Ching by Lao Tzu (Translated by Man-ho Kwok, Martin Palmer and Jay Ramsay) Flamenco! by G. Edwards and K. Haas Alphabet (History, Evolution and Design) by Allan Haley |

|

Lao Tzu riding ox |