|

Home |

|

Classes |

|

Syllabus / Styles |

|

Biography |

|

Poetry |

|

Photos |

|

Articles |

|

Labyrinths |

|

Storytelling |

|

Artwork |

|

Respects Due |

|

Contact |

|

Links |

|

...with a spirit of self-exploration |

|

Pennine Tai Chi |

|

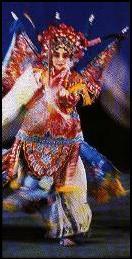

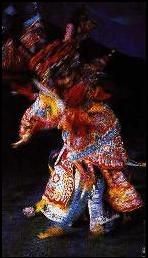

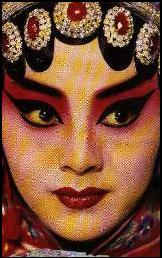

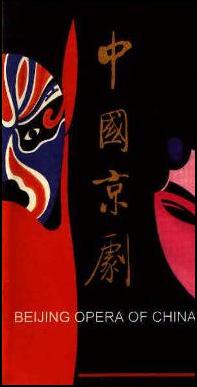

Beijing Opera (Jing Ju) |

|

When visiting China, many people will go to watch a performance of Beijing Opera. There are in fact many regional variations of Chinese Opera, but Beijing Opera or Peking Opera is by far the most well known. As well as singing and music, a typical opera will include such elements as dialogue, dance, acrobatics, martial skills and mime. Many operas last for three or four hours but nowadays you are more likely to see a performance of popular scenes excerpted from operas – rather like watching the highlights of a football match. Sometimes the operas are likened to a thread of linked pearls. In this analogy, the story is said to be the thread, whilst the individual scenes are the pearls. Thus, each scene is an integral part of the whole, and yet at the same time has its own subplot and can be staged separately. A performer’s training begins at a young age and involves many years of dedication to attain a high standard. However, not everyone who practices Beijing Opera wishes to take it to such a level, and it is possible to study this art for a shorter period. My first contact with Beijing Opera was in the early 1990’s; at this point I had trained in the martial arts for around twenty years. I found that the ‘Warrior Role’ of Beijing Opera encompassed many similar martial skills whilst also having a distinct flavour all of its own that was unlike anything else that I had encountered. Here were skills that I knew I would struggle to master and yet somehow this provided all the more reason for attempting to do so. During the 1990’s, the renowned performers and teachers Liu Fusheng and his wife Lu Zhaofang visited the UK on several occasions to teach at various International Workshop Festivals. Then in 1999, Rachel Henson, a friend who is trained in the ‘Woman Warrior Role’ and resident in Beijing, helped arrange for me to visit the Academy of Chinese Opera. During my one-month visit I undertook three hours a day of one to one lessons in various aspects of the ‘Male Warrior Role’. The rest of the day I had time to practice and also to explore much of the capital city. Beijing Opera is popular throughout many countries in the Far East and quite a few students visit China to further their training. Whilst I was there, three students from Korea, two students from Japan and myself, were resident in the simple basic accommodation of the school’s foreign students block. One to one tuition was possible because the school was on its summer break, so my teacher Master Liu was not otherwise committed. During term-time, the campus would normally be humming with the sound of musicians and singers practising and with the activities of all the various other performance disciplines being taught. During my stay, I concentrated mainly on learning the skills of several weapons: the double-ended spear, the sabre, the halberd, long tasselled sword and monkey king staff. Another area in which I was able to gain experience was in two-person fight sequences including a Beijing Opera speciality of ‘stage fighting in the dark’ described as the art of ‘seeing-not-seeing’. Master Liu was generous with his teaching, being willing to teach anything I was capable of learning. During the evenings, I was able to see several Beijing Opera performances at a variety of places including traditional theatres, theatres within hotels, teahouses and even in the grounds of an astronomical observatory that was originally built by Jesuits. Stories in Beijing Opera depict Chinese legends, myths, fairy tales, ghost stories, romances, as well as historical events. Some of these stories that we may be familiar with in the West include scenes from ‘Monkey – A Journey to the West’ and ‘The Water Margin’ both of which have had television adaptations that have been shown in the UK. Much of the Beijing Opera stagecraft is symbolic and many of the storytelling elements have their own language. For example, when actors circle the stage, it may represent having undertaken a long journey. The lowering and raising of the curtain may symbolise the passing of a night and hence a new day. Painted faces and elaborate costumes all show the character, status and dispositions of the players. It is through such symbolic language and the skill of the actors that the scene is set. This means that the scenery and props are minimal; rather the audience is transported into the situation and is free to use the range of its own imagination. A traditional adage says, “small as the stage is – a few steps can take you between heaven and earth”. Having this experience in Beijing Opera has made me very conscious of the immense skills of the performers and has given a great insight into the subtleties and language of the art. I would highly recommend any visitor to China to have at least one night at the opera. |

|

The Little Phoenix |

|

Beijing Opera Programme |