|

Home |

|

Classes |

|

Syllabus / Styles |

|

Biography |

|

Poetry |

|

Photos |

|

Articles |

|

Labyrinths |

|

Storytelling |

|

Artwork |

|

Respects Due |

|

Contact |

|

Links |

|

...with a spirit of self-exploration |

|

Pennine Tai Chi |

|

Peking Opera Training in China |

|

Amused surprise was many people’s reaction upon hearing that I was going to China to study Peking Opera. My first contact with it had been in 1992 when I met Rachel Henson who had just returned from training in China. I learnt some spearwork from Rachel and then later trained with her teacher Liu Fusheng on a couple of visits which he made to teach and perform in Europe. The more I saw, the more I was fascinated with the movement and weapons skills. These had many connections to the Tai Chi and martial arts which I had practised for many years and yet at the same time were so different, having a flavour all of their own which was distinct from anything else that I had come across. Rachel returned to China to train full time, and it was through her that I arranged my visit to train at the Academy of Chinese Opera in Beijing. Full time students usually attend the Academy for 4 years or more, after many years of prior experience. For myself it was merely a 1 month visit. Nonetheless it was quite an intensive training with 3 hours of daily one to one sessions with Liu Fusheng, specialising in the warrior role, weapons work and movement aspects of the art form.

What is Peking Opera?Although there is a specialisation of roles, a full training in Peking Opera encompasses more than just the movement and martial aspects of the opera’s many facets. Amongst the elements which it incorporates are: · music · singing · dialogue · mime · martial skills · acrobatics The music ensemble which accompany the opera usually consists of 6 – 12 musicians, playing wind, stringed and percussion instruments. Non fighting scenes are usually accompanied by wind and stringed instruments. Fighting scenes make great use of percussive effects (drum, gong, cymbals & clackers) Singing is not in everyday language, therefore a translation into Mandarin (and at some theatres into disjointed English) will sometimes be flashed onto screens at the side of the stage or into supplied headphones. The stage is usually bare of scenery and the use of mime or certain props may invoke a picture of the scene into the imagination of the spectator. For example, the holding of the hand in a certain position or moving a horsewhip in a particular way may indicate riding a horse, being stationery on a horse or leading a horse. The passage of time may take place in a symbolic way. For example, the taking of a long journey can be shown by the actor circling the stage just once. The change of time or place can thereby be enacted in an instant. Full performances often last 3 – 4 hours, but increasingly today there are theatres which perform extracts in palatable bite size pieces. These will usually contain action type scenes which are definitely more easily accessible for western audiences (and many modern Chinese audiences) than full operas with much dialogue and singing.

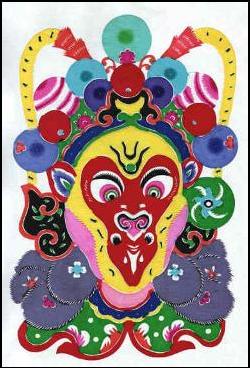

Some Well-Known Themes.Plays are often based on classic Chinese stories. Monkey KingA hugely popular character from the classic sixteenth century book ‘A Journey to the West’ by Wu Cheng-en. Monkey is mischievous, conceited and unpredictable yet at the same time retains a likeable quality. He is seen as representing the monkey or mischievous mind and human failings which can be redeemed through self development. |

Madame WhitesnakeThis Opera is inspired by a popular fairytale. It involves a strong Female Warrior role with some amazing scenes of spears being thrown towards the heroine who returns them all to the throwers by bouncing them off various parts of her body. The Water MarginThere are several operas taken from this famous novel which is based around a peasant uprising. Many will remember a television adaptation of this story which was shown on British television several years ago. The CrossroadsOne episode from this opera involves a case of mistaken identity in a darkened room. A fight scene ensues which is a masterpiece in mime, timing, synchronised movement, martial arts, acting and acrobatic skills. Some other inspirations for operas include romance stories and ghost stories. To reach a professional standard in Peking Opera requires a life of dedication. On the movement and martial aspects which I have encountered, numerous similarities and differences could be found with the Internal Arts. Here are just a couple of observations of each which stand out to me.

SimilaritiesRounded shape in body postures. In this aspect Peking Opera is closer to the Internal Arts than say Wu Shu, which has more straight lines. Many similar weapons – all having a strong emphasis on flowing movements and continuity of energy with a relaxed yet focussed feel.

DifferencesInternal Arts not predominantly for performance (although in competition and demonstration there may be a high emphasis on making the internal visible to an observer). Peking Opera involves a strong connection with an audience. This is often achieved through facial expression, eye contact and body posture, accompanied by accentuated music at certain focus points within the movement.

Linked PearlsThe Tai Chi form is sometimes referred to as linking together pearls with a thread – with the pearls being the individual postures and moves which are linked together to create the form. A similar analogy is used in Peking Opera. Here the plot or the story is said to be the thread, whilst the pearls are the specific scenes of the play. Each scene being an integral part of the whole but at the same time has its own sub plot and can be staged separately.

WeaponsAmongst the weapons used in Peking Opera are: · Spear (single and double ended) · Halberd (several variations in the design of its head) · Long Tailed Sword (I estimate that the skill required to use this is perhaps 10 to 20 times that required for the same sword without a tail) · Sabre (broadsword) · Staff (monkey is famous for his staffwork) · Horse Whip (not strictly a weapon, but requires similar manipulation skills) · Hammers (with dodecahedron shaped heads) I was able to gain some experience in all these except the hammers as time did not allow for this. Master Liu was generous with his teaching. He and his wife are renowned performers and teachers of Peking Opera within China and have travelled to teach and perform throughout the world. The Academy of Chinese Opera where I stayed is located close to Taoranting Park which is a popular place for early morning activities. From 6 a.m. the park was full of practitioners of numerous types of Chi Kung, Tai Chi, Pa Kua, ballroom dancing, line dancing, salsa dancing, joggers, skippers, backwards walkers, back rubbers, badminton players and much more. Later in the day, many people would meet here to play instruments and sing (often Peking Opera songs), or to play board games. I was lucky to find a group of Tai Chi practitioners who were very welcoming and happy to have me join them and to share their knowledge whilst working on open handed, sword and fan forms. Although my main path is in the Internal Arts, I feel that training in Peking Opera has enhanced my Internal Arts skills rather in the same way as when having a Chinese banquet and a dish with a new flavour arrives; this new dish can add to the overall balance of the meal.

|

|

Liu Fu-sheng teaching Dragon King Halberd |

|

The Dragon King in performance |

|

Papercut of the Monkey King |

|

Monkey King spins his staff |